In Yakutia, field work has been completed on Diring-Yuryakh as part of a large international project to study the ancient glaciers of Eastern Siberia. Among the questions that can be answered are not only the exact age of the ancient site, but also the age of the Lena River.YASIA met with scientists and found out how far they have advanced in the study of the monument.

As the Russian project curator Rejep Kurbanov, head of the Pleistocene Geochronology Laboratory at Moscow State University, said, the research covers not only the Lena River region, but also Kolyma, Yana, Indigirka. Their goal is to draw up a diagram of glaciations in Eastern Siberia in the early Pleistocene and to study the possibility of migration of people from Eastern Eurasia towards North America.

“Two years ago, Professor of Aarhus University (Denmark) Mads Knudsen drew international attention to the problems of Yakutia. A large group of leading scientists decided to study the history of glaciation in Eastern Siberia, the history of the Lena River, in a broad context, because this topic still remains unexplored. In this regard, we could not ignore the early Paleolithic monument of Diring-Yuryakh, since, among others, the question of whether people could live here in a problematic climate is important for understanding the overall picture. The solution of paleographic and geological problems will allow us to understand in many respects the possibility of human existence in Yakutia,” he says, adding that this year’s field research concerned mainly geological aspects. They, in the end, will allow not only to clarify the age of the monument, but also to simulate the conditions of existence of people at that time.

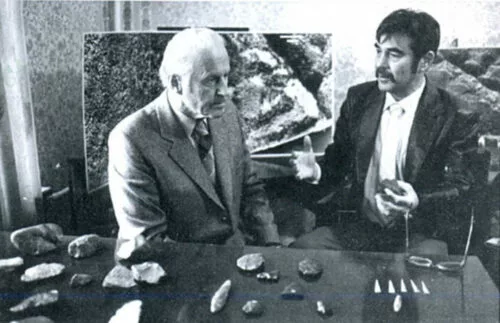

Yuri Mochanov demonstrates the Deering-Yuryakh collection to the famous Norwegian geographer Thor Heyerdahl

Man or nature?

Prior to that, scientists tried to clarify one of the key questions raised in connection with Deering-Yuryakh: is this archeology? From the beginning of the opening of the monument, there was no unanimity on this matter: not all scientists shared the point of view of the discoverer Yuri Mochanov that the object he found was a human site.

“Initially, there was a lot of discussion about whether the collection of objects from Deering-Yuryakh was Early Paleolithic artifacts, or stones split naturally, which Mochanov mistook for archeology. There were reasons for this. First, the general concept proposed by Mochanov assumed a very ancient age of the site, since he dated the monument 2-3 million years ago, which already provoked protests from archaeologists and geologists. The second problem is that the total collection of items numbered more than 5,000 items, and some archaeologists simply did not see real artifacts among this multitude of stones, and those who saw them said that they look like a rather late industry, and it cannot be 2 million years. As a result, the topic got stuck, and they avoided discussing it. That is, it was known that there was such a monument, but its archaeological characteristics and age remained unclear,” says Kurbanov.

Therefore, the first question that the project tried to answer – is Deering really an Early Paleolithic site of man? And today a clear answer has been received. At the initial stage of research, the entire collection obtained by Yuri Mochanov during the many years of excavations at Diring-Yuryakh was revised. An expert on the Early Paleolithic, Doctor of Historical Sciences from the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the SB RAS Anton Anoikin was involved as an expert. As a result, about 300 items were selected from the five thousandth collection, which do not cause doubts among archaeologists – these are products created by man. The rest of the items can also be artifacts, but their interpretation is not so straightforward.

Elena Solovyova from the Museum of Arctic Archeology. S.A. Fedoseeva demonstrates to Natalya Vikulova (Institute of Archeology RAS, Moscow) and Anton Anoikin (Novosibirsk) the collection of artifacts from Deering-Yuryakh

What was wrong with Yuri Mochanov

In the course of research in August this year, geologists once again studied the geological section of the Tabaginskaya terrace, where artifacts were found. According to Andrei Panin, Deputy Director of the Institute of Geography of the Russian Academy of Sciences, this section is interesting in itself, since it is the oldest known terrace.

“At the base of the section, first there are limestones, red sands lie on them – this is the ancient alluvium of the Lena River. If we can get the date for these sands, then perhaps we will find out when the Lena River appeared approximately. So far there is a preliminary date of 2-3 million years, but this date is already half a century old, and it is based on general geological considerations, since at that time there were no methods of quantitative dating of such deposits. Now modern dating methods are available to us, and, if successful, this will be the oldest material evidence that Lena existed several million years ago. I note that we have the opportunity to seriously study the history of this great river, in the next few years at the Permafrost Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Dr. Alexei Galanin will implement a large project of the Russian Science Foundation (21-17-00054) dedicated to this problem,” he says.

As scientists explain, drawing conclusions about the age of Deering-Yuryakh, Yuri Mochanov was based mainly on geological and geomorphological data, which later became one of the sources of criticism of his theory.

“On the surface of the red alluvial sands there are stones that differ in their composition from the rocks (limestones) lying under the sands, and it is clear that they were once brought by the river. And among these stones there are those processed by man. Above, there is also a layer of sand, but already others – grayish and yellowish. Yuri Mochanov also considered them to be the alluvium of the Lena River, i.e. believed that the monument lies inside the alluvium of the Tabaginskaya terrace. And since the terrace was dated 2-3 million years ago, he also dated the cultural layer,” says Andrei Panin.

Many geologists and archaeologists disagreed with this point of view. For example, the famous specialist in the Quaternary geology of Siberia Semyon Tseitlin and the discoverer of the early Paleolithic of Tajikistan Vadim Ranov, believed that the sediments overlying the cultural layer are aeolian sands, which are no older than 300 thousand years. Later, a similar point of view was expressed by American geologists working at Deering. Today there is an understanding that the cultural layer does not lie inside the alluvium, but on it. That is, 2-3 million years ago, the Lena River formed a terrace, but people could come there after 600 thousand, and after 1 million years. In other words, the age of the alluvium is not the age of the monument.

“We can pinch the date of the monument between the age of the alluvium and the age of the overlying sands. Actually, the Americans did just that and got an age of about 300-350 thousand years, but these dates were not final, since, firstly, the method they used did not make it possible to make more ancient dates. Another problem with the geology of Deering is that there are two layers of aeolian sands, Mochanov designated them as layer 6 and layer 14. Layer 14 is very young, from which American researchers obtained dates of about 20 thousand years, and last year it was confirmed in the laboratory of luminescent dating of Moscow State University-IGRAN by Recep Kurbanov. We do not know the date for layer 6 yet, we can only say that it is not younger than 300-350 thousand years. So: all the artifacts found lay exactly under layer 14, that is, a younger layer, which does not give us the opportunity to unambiguously close the upper date for the monument even 300 thousand years ago. To address these issues, this year, under the leadership of Nikolai Kiryanov and colleagues from the Arctic Scientific Center of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), an expedition to Deering was organized,” Panin continues.

Participants of the international project “The history of glaciation of North-Eastern Siberia over the last 500 thousand years” and the expedition of the Arctic Scientific Center of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) on Diring

Having once again studied the geological section, scientists voiced two possible scenarios. The first is that the Deering cultural layer was never covered by layer 6, and then the date for this layer cannot be used to estimate the age of the monument. According to the second, more optimistic scenario, layer 6 of ancient aeolian sands once extended to the place where the artifacts were found, but was then blown away by the winds, and a younger layer 14 formed much later in its place. In this case, the date of layer 6 may be used to determine the age of the monument itself.

To clarify the second scenario, scientists conducted research in two directions: they tried to find artifacts directly under the layer of ancient sands, and such finds were made, however, their interpretation is ambiguous, and they require further study. Further, they tried to find evidence that at one time layer 6 extended over the cultural layer. Examination of the section revealed a series of former ice wedges filled with light sand, which is not present at the top at the moment.

“Samples were taken from one wedge, and if it turns out that their dates are the same as for layer 6, this will be proof that it once extended to the entire terrace. That is, it will be a geological argument that the dating of layer 6 can serve as the upper (youngest) date of Deering-Yuryakh,” said Panin.

General view of the geological trench, which has been preserved since the time of large-scale archaeological excavations by Yuri Mochanov

Another question that geologists tried to clarify is the version that the so-called Deering artifacts are in fact geo-facts, that is, they arose under the influence of natural processes of freezing and weathering.

“Our colleague Alexei Galanin from the Permafrost Institute has a beautiful theory that the accumulations of stones appeared as a result of cryogenic processes. Indeed, this is possible, but in this case, we disagree with this for several reasons. Firstly, in the geological sections, we did not see traces of how these stones move upward. The lamination of the section is nowhere violated, but it should take place if the stones are pushed out under the influence of freezing.

Secondly, if this process had taken place, we would probably have seen in the section “creeping” stones that did not reach the top. This is also not the case.

And lastly, all artifacts are confined to the accumulations of stones. In total, there are about 50 such clusters in the Deering-Yuryakh area, and artifacts were found in 30. Aleksey Aleksandrovich believes that these are frozen medallions, that is, the structure of frosty soil sorting. This also happens, but we excavated several such clusters and found sands with undisturbed bedding under them. In addition, these accumulations could well have formed in the course of river processes, for example, as a result of ice unloading, when an ice floe with stones frozen into it gets stuck on a riverbank and then melts – a quite typical process for modern Siberian rivers. But it is possible that these clusters were made by people who collected stones in one place for some kind of processing. Moreover, stones as a raw material for the production of tools, apparently, became the reason why they came to this place,” Panin summed up.

Space and dates

After archeology, the second most important question is the exact age of the monument. The Americans were the first to try to sell Deering-Yuryakh using modern methods. In 1989, Michael Waters received dates about 300-350 thousand years ago, but later it turned out that for the method of thermoluminescence analysis he used, this is the ultimate dating. That is, its results indicate that the monument is more ancient than 300-350 thousand years, but how much older is unknown.

“We also made an attempt in 2019 to make absolute dating, using a more modern and progressive OSL method that we can perform in Moscow, and which confirmed Waters’s conclusions that the layer under which the cultural layer is at least 350 thousand years old. But we did not advance further,” says Recep Kurbanov.

When it became clear that luminescent dating could not give an answer about the age of the monument, they began to look for other ways, and settled on the method of cosmogenic dating, which is actively developing all over the world today. Currently, only about 15 laboratories in the world can perform measurements to determine the age of ancient archaeological sites with the required accuracy. One of them is at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, where cosmogenic dating is actively used to determine the age of glaciations, as well as to date archaeological sites. The cosmogenic method makes it possible to obtain very ancient dates, up to 5-6 million years.

“Deering-Yuryakh is a very important object for understanding human evolution and its development in Eurasia, since it is, apparently, the earliest and most northern on the continent. And the first problem that we want to understand in connection with our project, at what time did people live here: was it cold conditions, or a relatively warm time? The uniqueness of Deering-Yuryakh is also in the fact that it is directly related to the evolution of the Lena River, and from the point of view of geology, it is a very difficult object to study. That is why absolute dating methods will play such an important role in understanding the big picture,” says Professor Mads Knudsen, Head of the Cosmogenic Dating Laboratory at Aarhus University.

Cosmogenic dating is a relatively new method in geology, only about 30 years old. The essence of the method is in the study of cosmic radiation, which is formed as a result of supernova explosions, and then enters the Earth’s atmosphere. Reacting with atmospheric gases, it then acts on the surface of rocks and forms cosmogenic radionuclides that accumulate in minerals. Knowing the rates of formation and decay of various cosmogenic radionuclides, by their combination, one can understand how long ago some conventional stone was covered by a layer of another rock and ceased to be influenced by cosmic particles.

“Imagine that you have a surface with a cultural layer on it. At the moment when it is open, it will experience the effects of cosmic radiation, and cosmogenic radionuclides will be formed in it. If then some deposits cover this layer, then the penetration of radiation will stop and different atoms will begin to decay. Due to the fact that the decay rate is different, the ratio of atoms will change. Therefore, taking a sample, by the combination of radionuclides, we can tell how long ago the burial of these deposits took place. But this is in ideal conditions, in real life everything is not so.

For example, several cycles took place on Deering-Yuryakh: first there was a cultural layer, then it was buried by aeolian sands, then they were dispelled, artifacts were opened and again began to accumulate cosmic radiation. How many times this has happened, we cannot identify, and this creates problems for us. Therefore, we selected not only the cultural horizon, but also samples from above and below. With samples and dates from the underlying, cultural and overburden materials, we can create a mathematical model that will allow us to determine the time of formation of not only the cultural horizon, but also deposits above and below,” explained Knudsen.

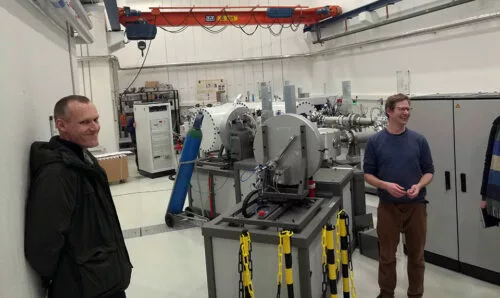

Professor Mads Knudsen (left) in the Cosmogenic Dating Laboratory. An accelerator mass spectrometer is used to determine age.

Now the samples have been sent to Moscow, where they will be processed in the laboratory of the Institute of Geography and then sent to Denmark for further dating. This is a complex and long process, most likely, it will take about a year.

“The method makes it possible to date deposits up to 5-7 million years old, but since Diring-Yuryakh cannot be so ancient, there is no time limit. If everything goes well with the samples, we will be able to determine not only the age of the cultural horizon, but also the age of all deposits, this will allow us to better reconstruct the conditions in which people existed,” he concludes.

The northernmost in the world

According to Professor Knudsen and his colleague Martin Margold from Charles University in the Czech Republic, the study of Deering will provide a more complete understanding of what was happening not only in Eastern Siberia, but also in Eurasia as a whole.

“Michael Waters singled out Deering-Yuryakh as the northernmost Early Paleolithic monument in the world, but 25 years have passed since its publication, but nothing fundamentally new has been done on this object. But during this time, a lot of work was done on the topic of climate change and whether it was possible for people at different periods to cross the Berengia to populate North America. Until last year, we believed that humans first appeared in America about 15 thousand years ago, and there is still debate on this topic. But last year there were two articles in Nature, in which it was suggested that they could have penetrated there earlier. And in this regard, Deering is interesting because it can provide new data on such a possibility,” says Martin Margold.

At the same time, Margold notes the duality of the problem. On the one hand, the possibility of migration largely depends on the climate: cold and glaciation are serious obstacles for this. On the other hand, in order to move to another continent, the sea level must drop in order for a land bridge to form, and this requires cold conditions that interfere with migration processes.

“We are working in Yakutia to establish the extent of glaciation, and to understand how they could hinder the migration processes from Eastern Eurasia to North America. Deering-Yuryakh is important in the sense that if we can get adequate results of absolute dating, we will pose the question: if people lived here hundreds of thousands of years ago, why couldn’t they wander into North America even then?” – he argues.

Thus, of the four main questions concerning Deering Yuryakh, one answer has already been received, in the near future scientists hope to answer three more: about the time and conditions of the existence of people and the ways of their migration.

“We need to understand what conditions people lived in: it was interglacial, or some kind of warming within the framework of glaciation, so that critics perceived that there was an opportunity for people to exist here. This will be done by the group of Professor Andrei Panin, they have already selected a variety of samples, on the basis of which the conditions will be simulated.

To answer the question of where people came from, it is necessary to find archaeological sites that are as close as possible in appearance to the Diring-Yuryakh collection. Anton Anoikin believes that two directions of possible migrations can be considered. This is a southwestern direction from Central Asia, through Altai and Baikal Siberia. So now in Tajikistan there are several Early Paleolithic objects of the age of 500-400 thousand years ago, whose collections have a certain similarity with Diring-Yuryakh in the technique of splitting stone and a set of stone tools.

The second direction is southern, from the territory of Southeast Asia, where there are also similar cultures of the Early Paleolithic. Archaeologists must carefully study the Asian collections, as well as all the oldest complexes of Southern Siberia, in order to more accurately answer the question about the origins of the early Paleolithic of Deering-Yuryakh,” summed up Recep Kurbanov.

Translation: Google

A source: Network edition “Yakutsk-Sakha Information Agency”